|

Take a winter walk through any neighborhood and you will see color from plants. It might take a little searching, depending on how urban or rural your walk is. Bark and berries add texture and contrast. Grasses and flowering plants add structure and do not need to be cut back until early spring. Their seed heads move with breezes, capture snow, and the structure gives shelter to wildlife through the winter. Different types of evergreen foliage soften bed edges and most ground covers bloom early.

Color is a useful way for animals to find food, such as berries. These shrubs and trees provide a food supply of berries throughout the winter. See how many you can spot on your winter walk. Winterberry Coralberry American cranberry bush Hackberry Serviceberry Witch hazel An excellent resource for deer-resistant and nonresistant plants: http://albany.cce.cornell.edu/gardening/deer-resistant-plants

0 Comments

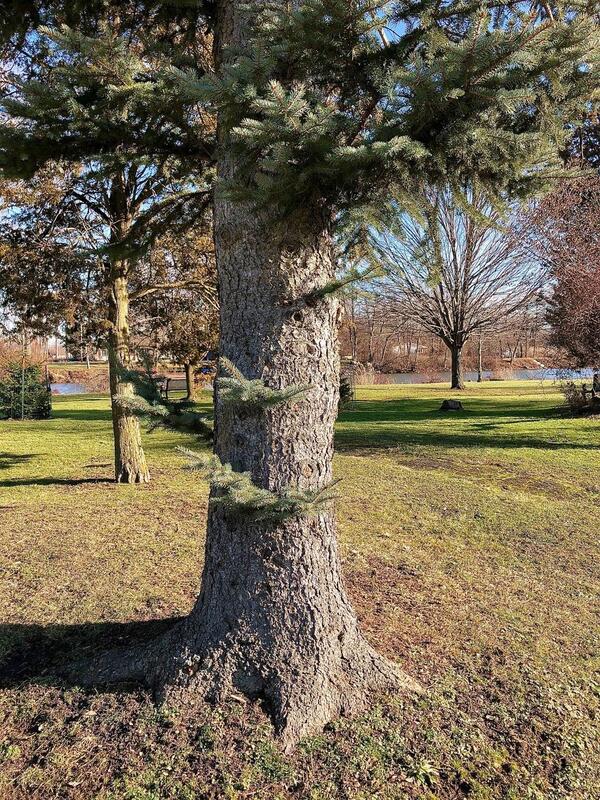

Winter is a beautiful time because the structure of trees and shrubs is exposed for us to see the subtle colors and textures in twigs and branches. Evergreens show different shades of green. Birds search for berries, remaining fruit on trees, and seeds from the clutch of seed heads left behind after summer’s blooms. A walk around North Tonawanda’s botanical garden gives us opportunity to notice what gardeners call “winter interest.” Plants with winter interest bring texture and color to the snowy and bare-branched landscape. Some plants have showy berries. Trees have interesting colors and patterns in their bark. Some plants bloom in the winter, offering tiny surprises to those who take time to notice. Our botanical garden has many species of trees with different bark textures. Compare the giant willow near Sweeney Street with small trees and evergreens. Evergreen trees and shrubs put on their own show. Varying shades of green are more apparent in winter, and berries can be blue, green, or red. Crabapple trees, some with yellow fruit and some with red, offer color contrast to snow and cloudy skies. They provide nutrition to foraging wildlife. The sweet gum tree shows its prickly seed balls against the winter sky. Winter beauty is everywhere.

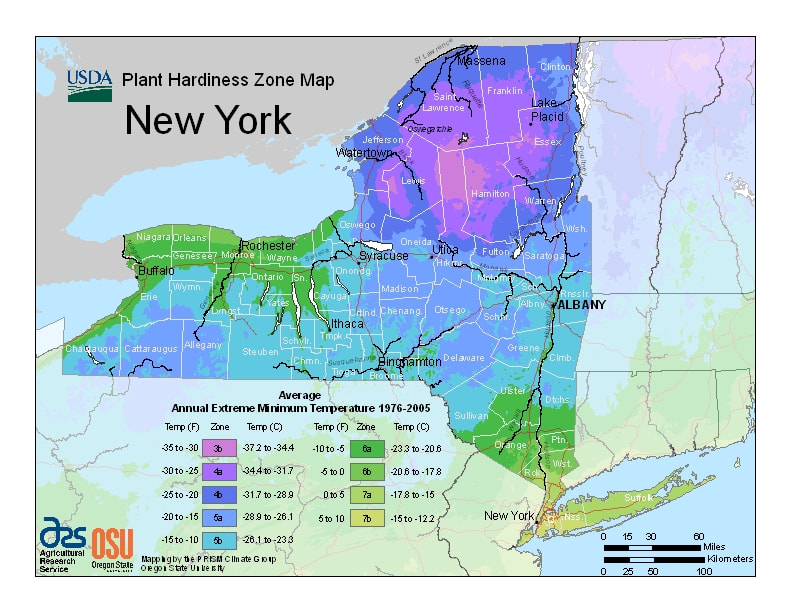

What do we notice in a garden in the winter? Animals searching for food, dormant plants, the impressive architecture of trees, and plenty of dead leaves immediately come to mind. We can best enjoy winter in the garden if we plan ahead. If you want wildlife habitat around your home, leave the area natural. Over-tidying takes away opportunities for animals to forage and to find shelter. Removing dead stems, leaves, and seed heads takes away natural habitats. Notice the different birds and animals during winter months and note how they use the area around where you live. Birds are interesting to watch. Having bird feeders attracts them, yet they will hunt for seeds if feeders are empty, and often they prefer to forage. At the botanical garden, we did not remove dead flowers of plants they prefer. Some common flowering plants that birds enjoy throughout our WNY winters are coneflowers, tickseed, Joe Pye, bachelor buttons, and black eyed Susan. Small birds will perch right on flower seed heads and enjoy a snack. Shrubs, trees, brush, and fallen leaves provide habitat throughout the winter for various animals. Using fallen leaves for mulch protects plants from wind and adds nutrients to soil. This local website has many good ideas for using autumn leaves. https://buffalo-niagaragardening.com/2019/11/05/its-leaf-season-9-tips-for-using-autumn-leaves-in-your-garden/ Helpful Links and Resources: https://ny.audubon.org/conservation/choosing-bird-feeder https://www.audubon.org/news/to-help-birds-winter-go-easy-fall-yard-work https://www.chicagobotanic.org/plantinfo/perennials_winter_interest  They are Plant Hardiness Zones. The USDA developed a map of the US with plant hardiness zones to help gardeners determine several important facts: https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/ First planting dates. First frost dates. Which plants are most likely to thrive at a given location. The average annual minimum winter temperature. Each hardiness zone is a geographic area that includes a specific range of climate conditions that are relevant to plant growth and survival. The USDA determined the zone boundaries based on the average annual minimum winter temperature, divided into 10-degree Fahrenheit zones. We are in Zone 6 here in Niagara County, and the USDA map shows that our county has further been divided into 6A and 6B. North Tonawanda is in 6A. We can use this information to determine if a plant we want in our garden will survive the winter or not. Sometimes a plant will tolerate zone 6A if it is planted in an area protected from winter winds and if the soil has good drainage. Local garden stores take this information into consideration when they choose which plants to offer for sale; however, a savvy shopper will look for this information on the plant tag. Some plants that we consider annuals are actually perennials in southern locations. A few examples are rosemary and lantana. These plants have woody stems and can be used as shrubs much further south. Likewise, plants that thrive here due to our cooler temperatures will suffer in the heat further south, such as peony and lilac. These links are references for this information as well as more in-depth explanations: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hardiness_zone https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/ http://essex.cce.cornell.edu/gardening/food-gardening/first-planting-dates http://ccenassau.org/gardening/soils-and-climate  Which is the better choice, annual plants or perennial plants? That depends on your preference. Perennial plants are economical because they return every year, but they usually flower for a shorter period of time. Annual plants usually flower throughout the growing season. Both can be very colorful, but annual plants produce flowers for a longer time within a growing season. Perennial plants tolerate dry conditions better, while annual plants require water and fertilizer to keep them blooming. Annuals can be replanted or changed each year, while perennials are more of a commitment to blooms the following year. An annual plant completes its entire life cycle from seed to flower to seed within one growing season. The entire plant will die at the end of the growing season. The seeds are the connection between each generation. Sometimes the seeds of an annual plant will survive our winter and germinate the following spring. The photo shows bachelor buttons, which have reseeded themselves in our butterfly garden. A perennial plant lives for many growing seasons. Often the stems and leaves will die back but the roots remain alive under the soil throughout the winter and will send up new shoots the following spring. Another type of plant is a biennial, one that has a life span of two growing seasons. During the first year, the plant will usually produce a small rosette of leaves, and the following year it will have a colorful show of flowers that produce seeds. Examples of biennials are foxglove, delphinium, primrose, and poppies. Since their seeds sprout the following spring, it becomes easy to have plants from either the first- or second-year cycle mixed in a flower bed, which makes it appear that these plants are perennials. Another variable to consider is our climate. Here in western New York, our plant hardiness zone or climate range dictates how well plants survive through the winter. Plants we consider annuals can be perennials elsewhere. Petunias, rosemary, and lantana are perennials in some southern states. So, how to plan your garden? If you use perennial plants, it is wise to know when they usually bloom. Planting perennials with different bloom times will provide a wave of flowers as the season progresses. Examples are crocus and daffodils in the spring, which grow from bulbs. Peonies, daylilies, cone flower, black eyed Susan, and chrysanthemums are examples of perennials that bloom at different times. Annual plants include vegetables, marigolds, petunias, and zinnias. Annual plants that drop seeds which survive our winters include cleome, cosmos, forget-me-nots, and bachelor button. Oftentimes nothing needs to be done with these seeds, as the seeds survive on the soil’s surface and will germinate once the sun warms the soil in the spring. Informative links from New York Cooperative Extension websites: http://ccesaratoga.org/gardening-landscape/annuals http://warren.cce.cornell.edu/gardening-landscape/lawns-ornamentals/perennials http://ccesuffolk.org/gardening/horticulture-factsheets/annual-and-perennial-flowers-bulbs-and-ornamental-grasses Sources: https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/wildseed/growing/annual.html https://www.hgtv.com/outdoors/flowers-and-plants/flowers/flower-power-annuals-vs-perennials Visiting the local plant nursery can be confusing these days. Public demand for native plants is increasing, yet a visit to your nearest garden store presents you with choices where you should understand the definitions before you choose a plant for your home. Cultivar, an abbreviation of cultivated variety, is defined as from the native species, a new plant was created either by natural cross pollination, natural mutation, people cross pollinating, or genetic modification of the plant. This new plant retains many of the original plant’s characteristics but may have more appeal such as larger flowers, different colored leaves, different flower colors, better growth habit, or better disease resistance. A nativar is a native cultivated variety, which means that it was naturally pollinated or created from native plant parents. Nativars can have the same characteristics as the native plants in that they are adapted to the same geographic region as the native species in regard to disease resistance, local weather, and local soils. However, nativars have less genetic diversity than the same native species, and the genetic changes can frequently cause changes that make the nativar unacceptable to wildlife species that depend on that specific native plant. For both cultivars and nativars, flowers can be sterile, leaves can be a different color, or nectar could not be as available to native creatures that depend on the native plant for food, a place to lay eggs, or as food for newly hatched larvae. Many birds such as goldfinches depend on flower seeds of native plants for their specific nutrition requirements. One example of a nativar is the different varieties of Coneflower/Echinacea that are now available to the public. The first photo shows a native coneflower. The other 3 photos are nativars. This information from the Maryland Cooperative Extension explains the issue well:

"The question is not whether it’s morally wrong to use cultivars, but whether they are good for ecosystem health. Sterile cultivars of native plants are benign; they can’t cross-pollinate with their wild relatives, so they pose no risk to wild plant populations. When cultivars are beneficial to ecosystems, they are good. For example, plant breeders are working to create disease-resistant cultivars of native tree species that have been hit hard by non-native invasive plant pathogens. If done with care, it is possible that such cultivars could be used to intentionally spread beneficial DNA into wild plant populations and help restore those species." https://extension.umd.edu/hgic/topics/cultivars-native-plants References: https://www.lewisginter.org/cultivars-nativars-oh-my/ https://extension.umd.edu/hgic/topics/cultivars-native-plants https://habitatgarden.info/home/plants/cultivars/ Let’s begin with a few definitions. A native plant species is one that occurs naturally in its ecoregion and habitat where, over the course of time, it adapted to physical conditions and other species in the system. A key point is that a specific plant can’t be called native without saying where it is native to.

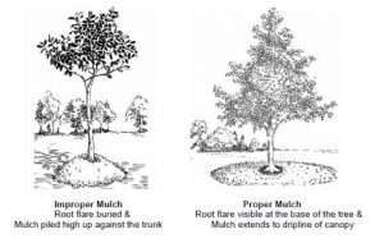

So, for a native plant species, we need to know its natural region and habitat. Natural regions can span several states and into Canada or Mexico, or they can be small areas with specific soil and climate situations. A red maple’s natural region extends over all states east of the Mississippi River, a few states on the western side of the Mississippi River, and into southern Canada. In contrast, the auricled twayblade (Neottia auriculata) grows in the Adirondacks high peaks. A non-native plant is called exotic, meaning that its native region and habitat are not here in our area. Many exotic plants come from similar habitats, so they grow well here. Wisteria, daylilies, hosta, and lilacs are popular examples. Some exotic plants brought to our area become invasive. When a non-native plant thrives in a location to the point that it takes over native plant habitats and chokes out other species, it has become invasive. Creeping Charlie, Japanese knotweed, and Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima, sometimes called China sumac), are examples that are all around us. It is very important to know whether an exotic plant is invasive. Here are a few websites that list invasive plant species of New York: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/ornamental-crops/greenhouse-resources/alternatives-ornamental-invasive-plants-sustainable-solution-new-york-state/ http://rocklandcce.org/environment/invasive-plants http://orleans.cce.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-nuisance-species/invasive-plants One of our best resources for plant and growing information is the Cooperative Extension service. Cooperative extensions have their offices in the county seat of each New York county, and their information is specific to that county. Niagara Cooperative Extension Service is in Lockport (716) 433-8839 x226 http://cceniagaracounty.org/gardening In the next post, we will learn about nativars and cultivars of native plants as well as the benefits of including native plants in a garden. SOURCES: https://extension.umd.edu/hgic/topics/what-native-plant http://orleans.cce.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-nuisance-species/invasive-plants http://ccecolumbiagreene.org/gardening/lawns-ornamentals/native-plants https://nysipm.cornell.edu/agriculture/ornamental-crops/greenhouse-resources/alternatives-ornamental-invasive-plants-sustainable-solution-new-york-state/ http://rocklandcce.org/environment/invasive-plants What is a mulch volcano? It is a large buildup of mulch, intentionally placed around the root flare of a tree and often up its trunk as well. A common practice visible in parking lots of commercial areas, these mulch volcanoes are done to make trees look pleasing and to suffocate weeds to reduce maintenance over the summer months. This practice creates a “lollipop effect,” where tree trunks appear to rise straight up out of the mulch.

Mulch volcanoes kill trees. This landscaping trend causes stress and difficulty for trees trying to survive in urban and suburban habitats. The popular PBS TV show, “This Old House,” produced an informative video showing what is in a mulch volcano and the damage this practice causes: www.youtube.com/watch?v=fI12XNNqldA Tree experts from Cornell, across New York State, and around the country have condemned mulch volcanoes as extremely harmful to the health of trees. s3.amazonaws.com/assets.cce.cornell.edu/attachments/22049/April_11_2017_volcano_mulching.pdf?149192 Consider that mulch does more than spruce up your yard. It could ruin your landscape if not done right. Your yard is an ecosystem, and death of a tree removes something out of the ecosystem, leading to consequences that could drop the value of your home. A walk in the woods will show you tree flares, exposed trunks, and tree roots living above ground naturally. The base of the trunk of the tree, whether newly planted or established, must be exposed and flare out. This is the basal root flare, the transition between the trunk and the root system. The root flare needs to be exposed to allow excess moisture to escape, preventing growth of fungus and minimizing rot and decay. Mulch can help a newly planted tree by keeping its root system covered, holding nutrients in the soil, hindering weed growth, and holding moisture on the soil line to keep young trees hydrated. Mulch prevents soil compaction, which is bad for root development, and it reduces the amount of freezing and cold exposure to the root system by insulating the ground. Mulch volcanoes begin as a newly planted tree needs coverage to protect its young roots and base. Placing too much mulch around the flare and trunk creates the first layer of buildup. The following seasons, as more mulch is placed around the tree's flare and trunk, the mulch mats itself together to form a barrier. The constricting layers of mulch bury those areas that naturally need to be exposed. As mulch volcanoes bury tree trunks and flares, moisture collects that leads to rot around these vulnerable areas. Once rot sets into the trunk and flare, bark and protective structures become weakened and exposed. The bark cracks, peels, or comes off, and internal structures are vulnerable to insects, disease, decay, and malformation. These all move in and slowly kill the tree. Mulch volcanoes have several side effects, including creating a compost pile, where the material becomes hot enough to kill the inner bark of young trees or prevent the natural hardening off period where trees prepare for winter. These mountainous monstrosities promote growth of secondary roots in the mulch rather than in the surrounding soil. Roots circle around the tree and can eventually choke off the main roots. In periods of heavy rainfall, the tree can drown or be more susceptible to rot due to the sponge-like nature of mulch. Heavy layers of mulch can be colonized by water-repelling fungi, which will actually turn the pile into a hydrophobic area, leaving the tree in drought conditions despite receiving water. The proper way to mulch around a tree appears more like a doughnut. The depth of the ring should be 2 to 4 inches at most. For soils that are poorly drained such as clay, only 2 inches of mulch is needed. Once the mulch is applied, pull the mulch away from the tree trunk by 5 to 6 inches. You should be able to see the tree trunk and the flare of the tree. The diameter of the mulch should extend to the drip line of the canopy. An important factor to keep in mind is that although mulch color will fade, this doesn’t mean we should top off the organic matter with a few inches of fresh material. Measure the mulch levels before deciding to add more, or you could end up creating a deadly environment for the tree. You may ask yourself, Just how much could I learn from a butterfly?

As urban and commercial development grows, natural wildlife habitats are disappearing. Many species are becoming endangered or extinct, or adapting to urban life. If you observe a natural habitat closely, you come to understand the delicate balances of our ecosystem. Butterflies make excellent observation subjects. To better understand a butterfly habitat, let's take a look at the life cycle of the butterfly. This life begins as one of many eggs laid on a plant by the adult butterfly. Many butterfly species are very particular about which plant they lay their eggs on, as this plant will provide food for the emerging caterpillar. This plant is called the host plant. The caterpillar emerges and feeds upon the host plant. Then in 2 to 4 weeks, it will cling to a twig or similar object and form a pupa (chrysalis), where it will spend about 2 weeks making a miraculous metamorphosis. Wat entered as a less than atteractive caterpillar will emerge as a cold, wet, limp adult butterfly. After an hour or so of sunning, drying, and pumping fluid into its limp wings, the butterfly is ready to fly. This drying period is a dangerous and delicate time for the butterfly, since it is easy for predators to catch since it cannot fly away. The adult butterfly spends its life sipping nectar, eluding its enemies, and seeking shelter from bad weather. The life cycle comes full circle as the butterfly mates and then seeks out the same host plant to lay its eggs. Butterflies need warmth, shelter, and food. Since butterflies are coldblooded, they can often be seen on rocks or dark logs during cooler temperatures, where the butterflies can absorb the sun's rays. Shelter such as crevices and the underside of leaves provide shelter from predatirs, wind, and rain. For food, butterflies have their favorites depending on their species. For instance, the Monarch butterfly caterpillar prefers milkweed. Butterflies need fresh water, which they get from very shallow pools or sand saturated with water. It is often easy to spot butterflies at the edge of puddles. Male butterflies can be seen in mud puddles. They are gathering minerals from the mud, which will help them to produce pheromones to attract female butterflies - consider this mud cologne! The butterfly garden at the North Tonawanda Botanical Garden is designed to attract many types of butterflies, since many different varieties and colors of flowers have been planted there for the butterflies to enjoy. |

Archives

January 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed